- One of the central terms in the Buddha’s teaching is citta, usually translated as “mind”. Cittais of fundamental importance to the practitioner, for when the Buddha speaks of bondage it is the cittathat is bound, and when he speaks of liberation it is the cittathat is liberated. In our practice we study the four domains or foundations of mindfulness (satipatthana), one of which is citta. It’s clear that cittais central to our practice. But what is citta, and how is it contemplated?

What is citta?

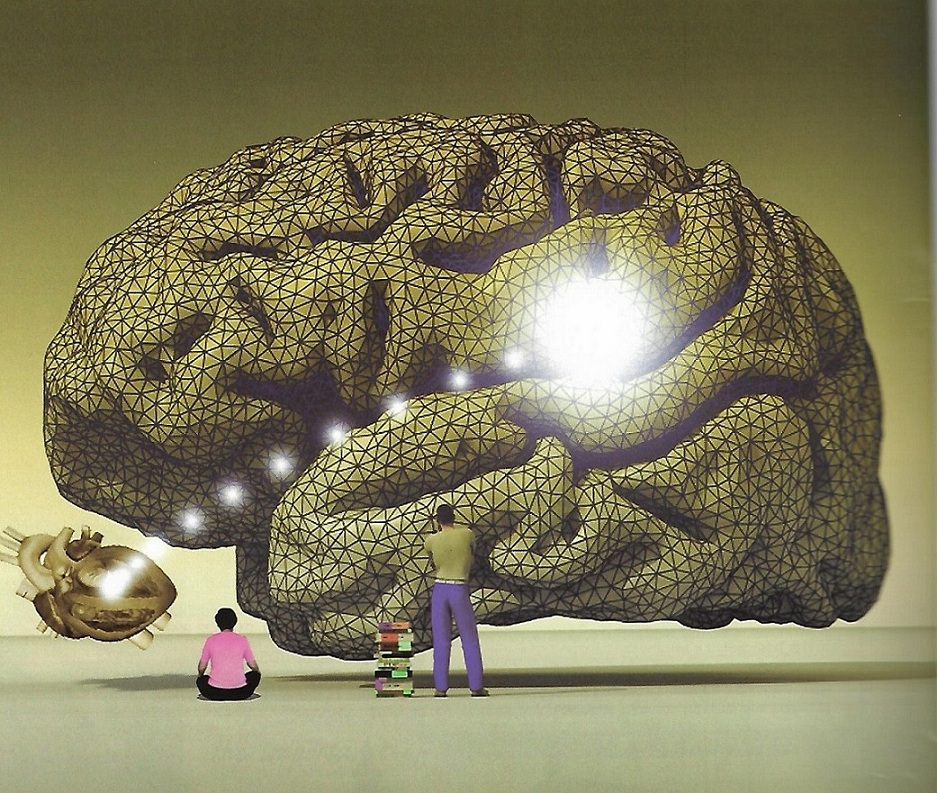

- While citta is traditionally translated as “mind,” this can easily give the wrong idea. For us, mind is what is found in our head, and it thinks. But if we were asked about the seat of emotion, we might indicate our heart. Often we feel that thought and emotion are at war with each other, constituting separate and conflicting domains of existence. But for the Buddha, they are not separate. Citta includes what we call “head” and “heart”.

- Citta is the aware centre of a person; the subjectivity that experiences. It could be translated “mind,” for thoughts are certainly part of citta. It could be translated “heart,” for emotion is inseparable from citta. It could even be translated “soul,” in the original sense of the alive essence of a person. Perhaps the best compromise translation is the compound “heart/mind”.

- Citta refers to our inner centre of subjectivity, the awareness at the centre of ourselves. We could see it as our sense of inner space, the inner domain within which we experience ourselves and our world. Some of our experiences clearly belong to the outer world. Seeing and hearing, for example, are in some way public. But other aspects of our experience, our thoughts and feelings, for example, seem to belong more to our inner world. This experienced inner world is citta.

- But we must remember that citta is not radically separate from the body. One term the Buddha uses to describe us is saviññanakaya, a “body (kaya) endowed with (sa) consciousness (viññana),” or “sentient body”. We are bodies, but bodies that experience, and are, in turn, experienced—by other sentient bodies. What does the experiencing? Citta. We are defined by this two-fold nature, both physical and non-physical, and our humanity necessarily includes both.

- In Satipatthana Sutta (MN 10), citta is not given an exact definition. It is used in a broad sense to indicate our general state: how we are, at this time. This is close to what we might call “mood”. Consider the routine greeting, “How are you?” Usually we respond automatically—”Good!” But what if the next time we were asked this question we stopped, looked within, felt our inner state, and then presented this in our answer. We would be presenting our citta. Of course, if we were asked this same question ten minutes later and went through the same process we might give a very different answer, for the citta is impermanent, process rather than substance, continually moving and re-forming.

Citta and Vedana

- Citta is closely linked to vedana, usually translated “feeling”. Vedana is the affective or hedonic aspect of experience. The noun “vedana” is derived from the verb vedeti, which means both “to feel” and “to experience”. The double meaning is important – feeling is inseparably bound up with experience. Feeling indicates both an aspect of experience and a way of experiencing.

- We could say vedana is the ‘flavour’ of experience. When we eat, we experience the physical sensations of food, its hardness, softness, texture, moisture, and so on. We also experience the flavour of food. The flavour is not the material sensations. It is intimately connected with them, but it remains distinct from them. And it is the flavour that moves us, that stimulates our response to food. We are moved to take more if the flavour is pleasant, to take less if it is unpleasant, and to indifference if we can’t find any flavour. In the same way, vedana is the flavour of experience, and experience always has an affective tone or flavour.

- What do we mean by “affect?” It is that which has the capacity to move us, as when we say “That was very moving,” or “I was moved by that.” Pleasant feeling (sukha vedana) moves us to hold, painful feeling (dukkha vedana) moves us to resist or reject, and when we don’t know what we are feeling (adukkha(m)asukha vedana) we are moved to dullness, doubt and confusion. But we are moved, because experience comes to us already affect-laden.

- Experience always contains feeling, for to experience (vedeti) is to feel (vedeti). In the teaching of dependent arising the Buddha says “contact conditions feeling”. “Contact” (phassa) is the immediacy of experience, and within this immediacy we find feeling. This does not mean that first we experience and then later we feel; it means that in experiencing, we are already feeling.

- The Buddha goes on to say “feeling conditions craving”. Craving is the usual translation of tanha, which literally means “thirst”. Craving refers to the deep sense of absence at the core of our being, our sense of ourselves and our world being not right, missing something. This sense of lack and inadequacy drives us to reach out to possess something, anything that might satisfy our thirst and complete us. We are thirsty, but regardless of how much we drink we are still thirsty, so we keep drinking.

- Our thirst is stimulated and guided by feeling. But the relationship between feeling and craving, unlike that between contact and feeling, is not necessary. It is possible to have feeling—to be moved by experience—without craving, and our liberation is to be found within this possibility. So in our practice we study the interplay between feeling and craving.

- This interplay concerns the way we respond to experience, understanding that we are moved and how we are moved. Things happen. How do we respond? What do we do about it? How are we driven, and what drives us? How do we become lost in our obsessions? The answers to these questions are found in what moves us, what pushes us from behind or lures us from beyond. And all this is bound up with feeling, and our response to feeling.

- Which brings us to the realm of ethics, for ethics is about our responses, the actions that we take, the choices we make in responding to what we think is going on. All of us are faced with the fundamental question of how we should live. And all of us come up with an answer to that question. It’s not necessarily something that we have thought through, but all of us are living our answer to that question, and that answer is our ethics. The question itself comes to us as and through feeling.

- So in contemplating feeling we cultivate an ethical sensitivity, a sensitivity to what we are doing with our lives. While meditation methods usually begin with contemplating body, we do not find this ethical sensitivity here. It begins with feeling. Further, since contemplating feeling shows us how we are moved or driven, it is intimately linked to the contemplation of citta.

Contemplating citta

- Contemplating citta involves developing a sensitivity to our heart, our inner state, knowing how we are moved to respond, to act. And when we speak of what moves us to action, we are speaking of the ethical quality or colouring of our heart, that which directly conditions the nature of our actions.

- How do we find citta? Citta is most easily accessible through vedana, the feel of experience. Hence the centrality of vedana in satipatthana. Vedana is the hinge, that which connects body with heart/mind. The practice begins with contemplating body, and body is accessible through feeling; we feel our way into the body. The practice matures with contemplating heart/mind, and our heart/mind is accessible through feeling; we feel our way into heart/mind.

- In brief, in contemplating feeling and heart/mind we cultivate a sensitivity to what moves us and how we are moved. We become aware of that which is kusala (wholesome; skilful) or akusala (unwholesome; unskilful)within the heart, which implies both the heart’s inherent quality and the skilfulness or appropriateness of this quality. Contemplating citta opens up to cultivating an ethical sensitivity that guides our life. What colours the heart? And how are we moved to act? In other words, how do we live? And what is moving us to live in this way?

-

How does a bhikkhu live contemplating citta as citta?

-

Here a bhikkhu knows citta accompanied by passion (saraga) as citta accompanied by passion, and citta free from passion (vitaraga) as citta free from passion. He knows citta accompanied by aversion (sadosa) as citta accompanied by aversion, and citta free from aversion (vitadosa) as citta free from aversion. He knows citta accompanied by delusion (samoha) as citta accompanied by delusion, and citta free from delusion (vitamoha) as citta free from delusion. (Satipatthana Sutta MN10)

- Often we stumble into the contemplation of citta through becoming aware of disturbing emotions: fear, anger, anxiety, irritation, desire, or whatever. These are examples of citta accompanied by passion, aversion and delusion, and they are an important part of our practice.

- The essence of this practice is sati, mindfulness or presence. Fundamentally, it doesn’t matter what is present; what matters is presence, and the quality of presence. If emotion is present, and strong, then emotion becomes our meditation object. And remember that in contemplating emotion we are concerned only with seeing and understanding the emptiness of emotion. We are not trying to solve our emotional problems. We are trying to understand that our emotional problems are empty. They are not me, and they don’t belong to me. They’re just natural process (dhammata), coming and going according to conditions. But to discover this, we must be truly intimate with them, holding nothing back.

- However, when we are precise with our awareness we can see that emotion is complex. Emotion can usually be found in the body. We cannot have the emotion of “anxiety”, for example, without some tightening in the body. And all body sensations have physical location, so we can speak of finding our emotions in the heart or in the gut. All emotions have an affective feel to them, a quality of pleasantness or painfulness, or vedana. And emotion usually includes a narrative going on in the mind, which provides the intentionality of emotion. If I am angry, I am angry at someone or something; if I am anxious, I am anxious about something. This intentionality appears in and as the narrative of the thought-stream, which feeds and is fed by the emotion.

- And finally, emotion has a felt essence to it, which is not body sensation, not the quality of pleasantness/painfulness, not the thoughts around it, but something deeper, beneath all these and giving rise to all these. The essence of citta is the sentient sensitivity at the core of our subjectivity. This is what we are aiming at in contemplating citta.

- In this contemplation we cultivate intimacy with the state of our heart, by cultivating an intimate awareness. This requires a soft touch. To go in too rough and hard smothers the experience. The hardness of our approach is an expression of our agenda, our determination to manipulate circumstances so they suit our self, the one who thinks she knows how the universe should be.

- This is the softness of pure witnessing, which reminds us of the link between mindfulness or presence (sati) and equanimity or balance (upekkha). Upekkha comes from the prefix upa, which denotes “nearness” or “close touch,” and the root ikkh, “see”. Equanimity is a close looking on, or intimate witnessing. Witnessing, so not getting involved; but witnessing intimately, from very close by. We know we have this soft touch when the witnessing is like cutting through soft butter, in contrast to the hardness we experience when caught in the solidity of craving and attachment—and of resistance.

- The citta is both subtle and compelling. It is not easy to work with it. But if we are talking about what can change the way we live, we are talking about contemplating citta, not contemplating body. We may gain great depth of awareness of the body, but not any understanding of the heart and mind. If we want transformation, we find it in our relationship to citta. This is where we find both bondage and freedom.

- Patrick Kearney is an Australian full time lay meditation teacher who has 30 years’ experience in Buddhist meditation, in both Zen and Theravada traditions He conducts retreats, workshops and classes around Australia. He teaches both the techniques of meditation and the theory that underlies them, stressing the importance of theoretical understanding to complement meditation practice.

He was in SBS to conduct a retreat. Although he taught the techniques of the Mahasi tradition, he emphasised that there are also other techniques for yogis to contemplate the four satipatthanas.